Category: Fashion

8. Notorious Bricolage! (1940)

IN the movie, ‘Gone with the Wind,’ (1939) Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh) insists that her Mammy should turn her dead mother’s green velvet curtains into a fashionable dress to visit Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) in jail.

20th century cinema audiences gasped in horror as Scarlett rips the drapes from the elegant windows at Tara. The action became the most celebrated moment of invention, of make-do and mend, in the 1940s, chiming as it did, with women who knew how to make knickers, out of parachute silk!

“I’ll never recover from that first look,” David Selznick told his friends after he saw Leigh emerge from the embers of the ‘Burning of Atlanta’ set, costumed and made up to land the part of Scarlett O’Hara. As a snob and producer of the century’s most successful movie, he recognised that this instant would be life changing in his bid for Oscar winning glory.

Moments like this are at the heart of spectacular revolutions in the worlds of Art and Design, when lightening flashes of inspiration stir imaginations to begin spellbinding journeys to fame and fortune.

Women watching the movie say of Scarlett O’Hara, she is ‘powerful’ first and ‘beautiful’ second. She is determined to save Tara, her family’s cotton-growing estate in Georgia and like American pioneers was prepared to kill to defend her property.

To succeed, she has to take on male values and use her femininity to negotiate a power base while ceaselessly seeking the sexual fulfillment at the heart of the film’s romance.

She rips down her mother’s curtains to have them modeled as impressive, luxurious clothes to visit prison-bound Rhett Butler. She needs to borrow money to pay the taxes on Tara. It is not just an interesting piece of bricolage, Katie Scarlett O’Hara Hamilton is making ready to attack male bastions of barter and commerce with trappings of fetish and desire.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Camille Paglia leads a new generation of ‘Equity Feminists’ who are keen to throw off the acrimony between the sexes which began in the 1950s. While supporting equality before the law and the removal of obstacles to women’s advancement she also opposes special protections for women.

Paglia maintains that her reforming wing of Feminism is growing and gathering momentum from younger generations who are not in sympathy with judgemental, anti-pleasure, 20th century Feminism. It is my belief that the character of Scarlett O’Hara, supported by Rhett Butler in the film Gone With the Wind, is the prototype for our post-Feminist woman and that the film set the scene for romantic, feminine, provocative dress, emphasising the differences between men and women’s body shapes.

It’s a tiara! It’s a tiara!

AUDREY HEPBURN starved with thousands of others in Holland during the second World War. Despite being neutral, the Netherlands in World War II was invaded by Nazi Germany on 10 May 1940, as part of Fall Gelb. On 15 May 1940, one day after the bombing of Rotterdam, the Dutch forces surrendered.

The teenage Hepburn danced to raise money for the resistance movement in her father’s occupied land. Moving to London, and on from the horrors of war, she later recalled, “I remember the Fifties as a time of renewal and of regained security. Postwar austerity was fading and although the heartbreak remained, wounds were healing. There was a rebirth of opportunity, vitality and enthusiasm. The big American musicals came to London; people packed the theatres to see the twice-nightly shows of High Button Shoes, South Pacific and Guys and Dolls.’

It was her appearance as the curious, restless, Princess Ann in William Wyler’s ‘Roman Holiday’ in 1953 which changed mass women audiences’ lives for the better, forever.

‘I’ve never been alone with a man before’ the fictional Princess Ann (Audrey Hepburn) tells the newsman Joe Bradley, (Gregory Peck). For the audience, there is dramatic irony, realising that an heir to a throne is wearing borrowed pyjamas. He only realises who she is when he hears the news about her disappearance, next day.

In a scene between Joe Bradley and his editor they discuss angles and trends. ‘Youth must lead the way,’ he is told. In 1953, this was a topical theme in the context of access to a young princess. Her observations, on world conditions, would be worth a fee to the journalist, of $250, but her ‘views on clothes worth a lot more, perhaps a thousand’.

From that cinematic moment on, Audrey Hepburn would represent the dynamic interaction between Fashion and class structures. It was to be both her on and off-screen character; a role in which she would demonstrate how position in society dictates how Fashion is consumed.

Her interest in clothes, theatre, her sense of nostalgia and her relationship with the French designer Hubert de Givenchy created the legend which she and her films became. Givenchy said of her, ”She was capable of enhancing all my creations. And often ideas would come to me when I had her on my mind. She always knew what she wanted and what she was aiming for. It was like that from the very start.’

Favourite things….Audrey Hepburn and Breakfast at Givenchy’s

ONE magical turning point in Fashion’s fortunes was the release of Audrey Hepburn’s first significant Hollywood hit, ‘Roman Holiday,’ 1953. In Roland Barthes, Mythologies, his devastating take on consumerism and audiences, he describes Audrey Hepburn’s face as an ‘event.’ She had starred in only four major Hollywood films when she caused the French maestro and dilettante such sensation.

Barthes was proposing AH could represent meaning to audiences beyond those who watched her movies. After her most significant films were released, in the 1950s and 1960s, she became an influence on Fashion followers in Britain and America, encouraging women to use home dressmaking in the class struggle. As 21st century fans view Roman Holiday, Sabrina, Funny Face and Breakfast at Tiffany’s they witness the face that launched a thousand web sites and her popularity persists through digital media.

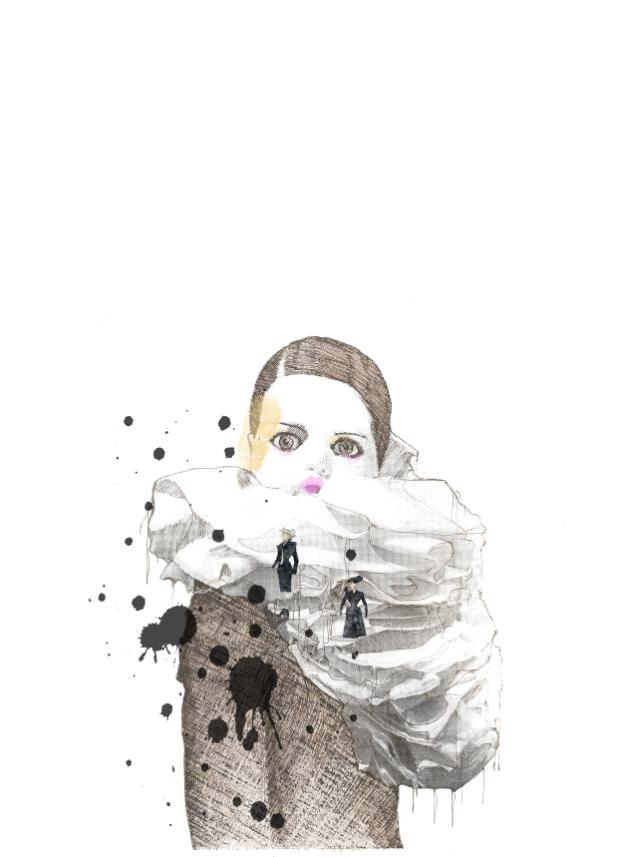

Audrey Hepburn stars in the second chapter of ‘FASHION MEDIA PROMOTION’ the collaboration between me and wonderful, Fashion illustrator and teacher, Anton Storey. ‘Vacanze Romane’ is based on a postcard, I had lying around. It was absolute genius for Anton to put the words from the back of it, which happened to be in Italian, across the main image. Super commissioning editor, Madeleine Metcalfe, who put her faith in me, also adored this pic. It was pinned above her desk when I visited her at Blackwell’s in Oxford.

At the political heart of ‘Roman Holiday’ is the script by Dalton Trumbo, part of the Hollywood Ten, the 10 motion-picture producers, directors, and screenwriters who appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee in October 1947, who refused to answer questions regarding their possible communist affiliations, and, after spending time in prison for contempt of Congress, were mostly blacklisted by the Hollywood studios.

‘I’ve never been alone with a man before’ the fictional Princess Ann (Audrey Hepburn) tells the newsman Joe Bradley, (Gregory Peck). For the audience, there is dramatic irony, realising that an heir to a throne is wearing borrowed pyjamas. He only realises who she is when he hears the news about her disappearance, next day. In a scene between Joe Bradley and his editor they discuss angles and trends. ‘Youth must lead the way,’ he is told. In 1953, this was a topical theme in the context of access to a young princess. Her observations, on world conditions, would be worth a fee to the journalist, of $250, but her ‘views on clothes worth a lot more, perhaps a thousand’. From that cinematic moment on, Audrey Hepburn would represent the dynamic interaction between Fashion and class structures. It was to be both her on and off-screen character; a role in which she would demonstrate how position in society dictates how Fashion is consumed.

The birth of the Cult of Cool

AFTER months of misery the Fashion industry usually fights back and there is delight in dressing up and going out. Paris, with its years of austerity, rationing and separation, during WW2, was revitalised by Christian Dior, Art director, dilettante, Europe’s other famous Norman.

With four years of Nazi rule Paris, ‘city of lights,’ was dim, but after liberation by the American forces there was the discovery of be-bop. It swept the city and black Americans stayed on, rather than return to the segregated USA.

On the streets the cult of cool was about to be born, and women wanted a designer to help them shake off the ‘horrible overalls’ and the boxy shapes of war-time clothes. They wanted to look sexy and feminine. It was then, in February 1947, that 30, Avenue Montaigne would become the world headquarters of Fashion.

Half a century before the internet Christian Dior, who had spent much of the war dressing the wives of Nazi officers and French collaborators, revived pre-war looks for post-war customers targeted at Hollywood’s world wide audience. He created feminised ‘flower women,’ happy to turn their backs on careers and military uniforms.

Dior’s New Look, in 1947, made every other dress look outmoded. There was an electric tension – ‘wasp waist of jacket, weight of skirt barely worn by human beings, real old fashioned corsets to create shape,’ in direct contrast to the 40s look.

Dior’s New Look, in 1947, made every other dress look outmoded. There was an electric tension – ‘wasp waist of jacket, weight of skirt barely worn by human beings, real old fashioned corsets to create shape,’ in direct contrast to the 40s look.

Christian Dior’s publicity machine was so effective that in a Vogue feature, proposing numerous routes through Europe by car by inventive motorists, Dior was featured by the magazine rather in the way Alexandra Shulman writes of Victoria Beckham for Vogue UK, April 2008.

Dior’s New Look was very good for fabric manufacturers, and especially good for his sponsor, Marcell Bussac. The ‘Bar’ suit, famously photographed by Willy Maywald. With its padded, static jacket and its heavy 80lbs, long, black wool pleated skirt, depended for its sculptural form on the 19th century skills of the corset maker. Coco Chanel said of her rival: “Christian Dior doesn’t dress women. He upholsters them”.

Dior became the ‘master of marketing;’ selling perfumes, and realising the ‘importance of the public identifying with the designer.’ Dior had his personal and business journeys mapped and followed by the Media, becoming the first celebrity couturier. Recognising the importance of trade between the House and buyers by 1948, he and his team include Cuba, Finland, Holland, Mexico, and Sweden in their contact lists. When Bettina Ballard, the journalist who was editor-in-chief of Vogue, America in the 1950s, heard that designs were being geared towards department store owners’ wives she said, “I would not put it past Dior!”

The recovery of the French Fashion industry was in the hands of Dior, who saved haute couture in the face of a ‘growing market of ready to wear, especially in the United States’. Paris was put into a position where it was also able to set the template for London couture and Fashion training. During the war there was the fear that American design would take over. So the Paris group, Chambre Syndicale, put together ‘Theatre de la Mode,’ a collection of dolls which were on display during the V&A exhibition in London. Said, to have been designed to raise funds for war victims they, really, were commissioned to raise the profile of Haute Couture.

CHUCK OUT THE DIRNDL, THE WALTZ AND THE WIGS

IN Vienna’s streets there are no musicians. Just attractive girl students in brocade breeches and 18thC wigs, handing out leaflets on Mozart and the Strausses. Not even Richard, at that!

Playing lead roles in the creation of a city, Fashion shops draw on the identity of designers and promote emerging talent. It hasn’t happened in Vienna. The sharply dressed Viennese couple, photographed here, at Dusseldorf airport, were shopping for clothes in Italy.

Observing the conservative internationalism of Vienna’s shopping quarters it seems it’s the dirndl and the waltz which stops Vienna becoming a Fashion city. It’s trapped by its history.

In the plush red restaurant at Hotel Sacher there appears a couture dirndl in soft red wool, with broderie anglaise blouse, sported by slim, elegant, still blonde matron. ‘Wanderlust and Lipstick’ sells the whole kit, the Alpine coats, the edelweis motifs to absolutely everyone; worn for parties, weddings, national celebrations by all the young dudes!

Although Fashion is about status, money, and pleasure, in Austria’s capital, with its history of political upheaval and revolution, home of psychiatry and modern erotic art, there’s a more measured, less frenetic, approach to our seduction to shop.

With the ‘glittering’ German designer Phillip Plein, Mondial, COS, Musette, Girbaud and True Religion on view and on sale, script-writers hope that avant garde Fashion, represented by Dries van Noten and Ann Demeulemeester, will be setting the scene alongside a ‘steady stream of young designers’.

Yet set up to please middle-aged, middle-brow tourists from home or abroad, not even Westwood’s post-modern ‘if only everyone wore the dirndl there’d be no ugliness!’ influence, on her protegee Lena Hoschek can halt the old world, ‘Austrian-ness’ celebrated everywhere. Hoschek’s clothes are probably not ironic enough.

Klimt does wonderful business in ties, scarves, trays and books outside the Imperial Palace in Belvedere but Austria’s lasting legacy for the Fashion world might be Sacha Baron Cohen’s camp, lederhosen-wearing travesty Bruno – the world’s most foolish Fashion critic.

Manchester, Paris and Montauk

HAVING appeared in Paris, the night before, Rufus Wainwright told an enraptured Manchester audience that Jean Paul Gaultier had let him ‘borrow’ the slinky black leather ensemble he was wearing for the show.

Making an entrance in sparkly ostrich feather cape over tails, he told us he would be giving us three opportunities to marvel at Gaultier’s work. Removing the fabulous feathers after his first two songs, then the coat and later a short bolero to reveal clinging body-hugging dungarees. Sitting with some difficulty at the grand piano he described the designs as not too practical for playing musical instruments, adding that was probably why Madonna could wear as much JPG as she liked!

Why, oh why, after a show full of talent did it devolve into a camp fiasco for a well-rehearsed encore? Well known Jewish singer, song writer, Adam Cohen and Wainwright dressed in short white togas with shiny blonde wigs looked uncomfortable and cold, even with oiled legs! Backing singers Cristal Warren and Stella Blackman, accomplished soloists in their own right, were dressed as pantomime cut-outs, certainly undermining their contributions to the musicality of the show. Maybe I’m not sure that ‘glad to be gay’ shouldn’t be tempered with patrolling by the style police. The image of Wainwright, above, at the piano with the show’s stunning and subtle lighting plots is the one I’ll take home with me.

Audrey Hepburn and the Big Bang Theory

WITH crowned kings and queens and actresses wearing tiaras, no-one’s too sure about jewels as status symbols anymore. But as Sheldon’s girlfriend discovers her, diamond-studded, apology gift, the worlds of fantasy and reality collide. See video below.

There’s more than just a tiara linking Audrey Hepburn, outside Tiffany’s in that hit 1961 movie, and Mayim Bialik as Amy Farrah Fowler in my favourite sit com, The Big Bang Theory. I can hardly write this blog for wanting to view the Youtube videos below. That’s not part of the connection, although it may be.

Audrey Hepburn frees modern woman to be more herself, than she has ever been before, as she steps out between New York skyscrapers from a yellow cab in the early hours of the day. Gazing into Tiffany’s window, ‘nothing really bad could happen to you there,’ holding her portable coffee, taking a bite from a do-nut, wearing tiara and pearls, we are convinced that anything is possible at any time.

When Amy is offended by Sheldon’s dismissal of her scientific journal article and he is persuaded, by Penny, to give her a gift, he chooses a tiara. For him this will be far more confusing than understanding String Theory! Yet without the Hepburn film moments, from the 1950s and 1960s, none of us would be able to get the ironies in the situation, either.

Before Hepburn in Roman Holiday, when Princess Ann realised she could lead a more ordinary life, even if for only one day, and in B@T’s when Holly Golightly throws off mid American domesticity for the glamour of New York, we did not know we could question status. From then on we could play with symbols, such as tiaras, to create our own individual personas through Fashion. We now, no longer, have to be either feminine or Feminist. We can be both!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1JfS90u-1g8

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8i_WpYc3YI4

Magic, Miniskirts and Modish Queens: an exploration of fashion over the royal Jubilee

“In 1952, when the lovely young Queen Elizabeth came to the throne bringing with her a revival in Tudor-style bodices and modest high collars, Marilyn Monroe was shocking the world by appearing in a calendar in just a bikini top and a pair of Levi’s.

Fashion Media Promotion: the new black magic looks at how fashion, as an industry, has adapted itself over the last 60 years to always command an important role in the global marketplace. It explores how, through communication methods such as advertising, digital and print media and cinema, fashion has waved its magic wand and entranced the whole world.

Revelling in the nostalgia of some classic fashion firsts since the Queen came on the throne, Fashion Media Promotion explores, with some humour, the impact of quintessentially British designers such as Mary Quant, Paul Smith and Vivienne Westwood on both British culture and fashions abroad.

This insightful book will appeal, one trusts, to fashion students and lovers, film buffs and writers as it searches every corner of the fashion world’s monopoly, from the inspiration of Hollywood classics such as Gone with the Wind to a critique of Roland Barthes’ promotional work.

The book, published by Wiley-Blackwell, includes 60 original full colour illustrations. Images of Audrey Hepburn’s glamour, Mary Quant’s Mini-skirts to Kate Moss’s androgynous appeal really bring to life how fashion has evolved over the decades.

“I have always been fascinated by how fashion links the generations and this has never been more the case than over the last 60 years. To keep us talking about it, fashion always has to find new ways to shock and thrill people, yet it also draws on past trends. Today a granddaughter might envy the clothes her grandmother used to wear in the 1950s.”

http://www.hud.ac.uk/research/researchnews/fashionintheageoftheimage.php

Fashion loves Controversy

Fashion loves controversy. When the ‘Devil Wears Prada’ came out, in 2003, Lauren Weisberger was regarded as a disloyal spy, who had ratted on her employers. The New York Times called the The Devil Wears Prada ‘trivially self-regarding’ and ex-colleagues of the fledgling writer, at Vogue, asked themselves the question, ‘Why should we publicise this thing?”

After script-writer, Aline Brosh Mckenna, had worked her magic, on the film version, (2006) and Meryl Streep had given a finely balanced performance as the brilliant Fashion editor, Miranda Priestly, then, perhaps, the interloping intern, Weisberger, was, partly, forgiven.

I did not expect my book to cause any such ripples. How wrong I was. Christian Dior’s Wikipedia page is currently running a line, quoting ‘Fashion Media Promotion, the new black magic’, saying that the designer was not the only Parisienne making clothes, for Nazi officers and collaborators, during the German occupation in WW2. That anyway they were doing it to keep the French Fashion industry afloat.

Fans of ‘Gone with the Wind’ hate the idea that costume designer Frances Tempest thinks the clothes were not democratically designed and that a ‘particularly repellent Salmon pink’ was featured.

A curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art loathes my tongue-in-cheek description of Malcolm McLaren, as a Dior-scholar, and the irritating computer misspelling of Karen Dunst’s name makes one of her fans furious.

These petty squabbles and angst are a stroll in the park compared to the Vivienne Westwood museum fiasco, filmed on British Style Genius. We may all be too polite, and subtle, to raise it, but I’m still holding my breath!