Category: Galleries

Mary Quant – Modernist Genius

MARY QUANT’s success came from being the empathetic, inspired, daughter of two first class honours graduates from 1930s Modernist Cardiff University. She also could not find clothes she liked for herself in 1950s London!

When I met her colleague, David Wynne Morgan, (Hill & Knowlton) in 2008, before he started to talk about MQ he said one word, “Genius.” So I was well tee’d up to write, ‘Mary Quant and the JC Penney blockbuster.’ “Fashion, Media, Promotion,” 2009.

Mary Quant fascinates people as people fascinated Mary Quant. Fashion feeds from her fervour, her love of fun and clothes. The industry admired her because she understood its strategies. Yet it was the British Post Office, which signalled her greatness; putting a little black dress on one of a series of stamps, celebrating 50 years of Modern design in 2009. No one was more surprised than Mary Quant when she found herself in the company of celebrated 20th century Modernists.

Successful at the promotion of Fashion, like Westwood coming from Art and not Couture, she was seen as innovator rather than designer. She refused to take credit for the mini-skirt, knowing it was, partly, from the street and that everyone, including André Courréges, was hacking away at hemlines in the Sixties. It is the impulse towards Modernism, which gave her the power to transform lives through Fashion; its optimism informed her biography and continued to inspire her thinking.

“Where glamour and romance meet”

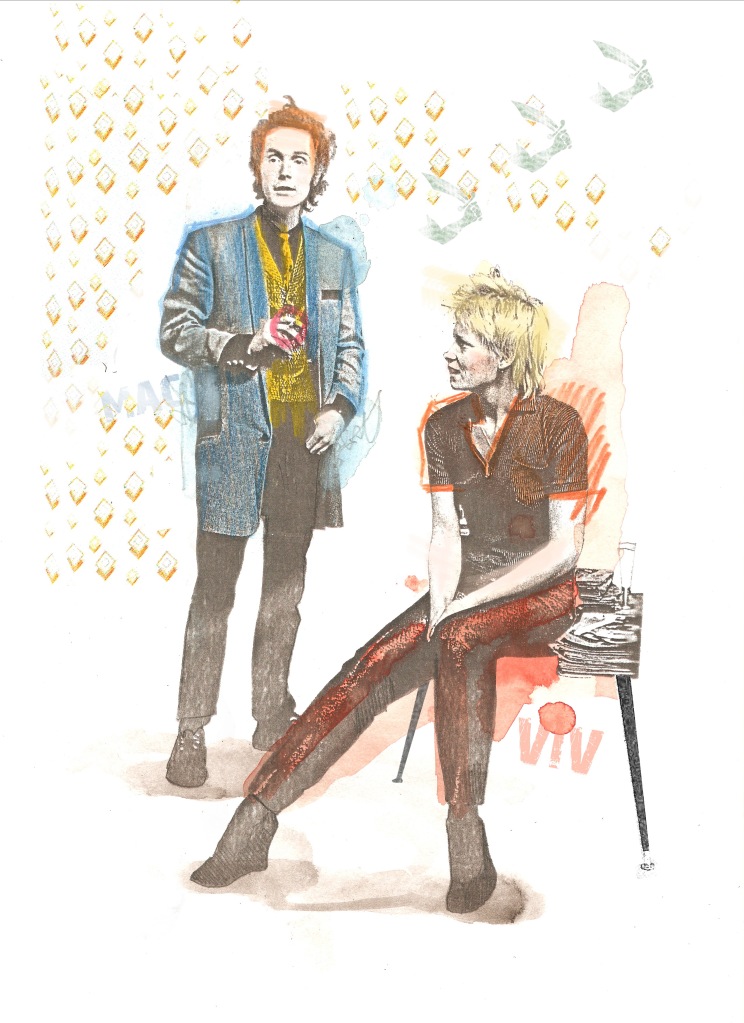

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD was a feminist, a revolutionary, a perfectionist, a silversmith, an innovator and an iconoclast.

She wanted her clothes to be seen, not as hers, but as belonging to and being worn by, ‘beautiful women.’

Her fashions have a transformational quality; they carry symbols, they provoke intellectual consideration.

NOTES from Claire Wilcox’s V&A superb solo exhibition video, 2008.

Westwood spent a lifetime teaching and learning. Anyone watching was in for a treat; hearing gentle, educated Derbyshire voice sharing newly minted ideas next to VW’s curated art. I was in heaven.

She experimented….’using very high heels, to lengthen legs, immediately, and round the bottom, the waist and top half of the body, ‘the thorax,’ is made to look tiny. Then, with a décolletage created using corseting techniques, from 200 years ago, and beautiful tight tailoring, the silhouette resembles ‘an ant on stilts’.

She explained that the head comes out, looking more important, and that the shoes form a pedestal to give particular power and expression to the most erotic part of the person, the face.

Her collections start from tailoring, essentially part of man’s dress. Her inspiration comes, in an especially English way, from when ladies adopted gentlemen’s Fashions.

Westwood told us, “In the West there is a complimentary exchange between English tailoring and French couture; with lots of trouble taken, attention to detail and everything fits perfectly.”

“Essentially this is the point in Fashion where glamour and romance meet, when there is something people have never seen before, but is like a perfume, which carries connections of something people knew already.”

Westwood describes her method as ‘synthesising things from the past’. As she works with today’s fabrics, she realises, there is the possibility of using them in ways not explored before, arguing that; ‘Fashion is the manipulation of materials.’

Inspired by Balenciaga and Dior, whose looks were part of her youth, she remembers how, in the 1950s, proportions were changed.

She notes that then, the hip was pushed forward, the back curved and the nose was going up. She reinvented this image, using a cage and putting fan pleats over it, suggesting that the silhouette can be distorted in other ways.

Recognising that in her career she has dealt with traditional and archetypal beauty in both clothes and in models, she states her philosophy:

“Having had the privilege, for 20 years, of working in Fashion I have never diffused or dispersed my vision – always keeping to the heart of it. It is a criticism against everything else. I am comfortable in assuming this arrogant position because I am so appalled by the banality of everything else. If I do achieve an influence it will be something very, very worth while spending my life doing.”

She may not have known how much this obsession [with Fashion] would become the backbeat to the rest of her own professional life. She describes his [Malcolm McLaren’s] encouragement, as they created the bleach, razored, prototype Punk hair, said to have influenced David Bowie, saying, “He took me by the hand and made me more stylish.”

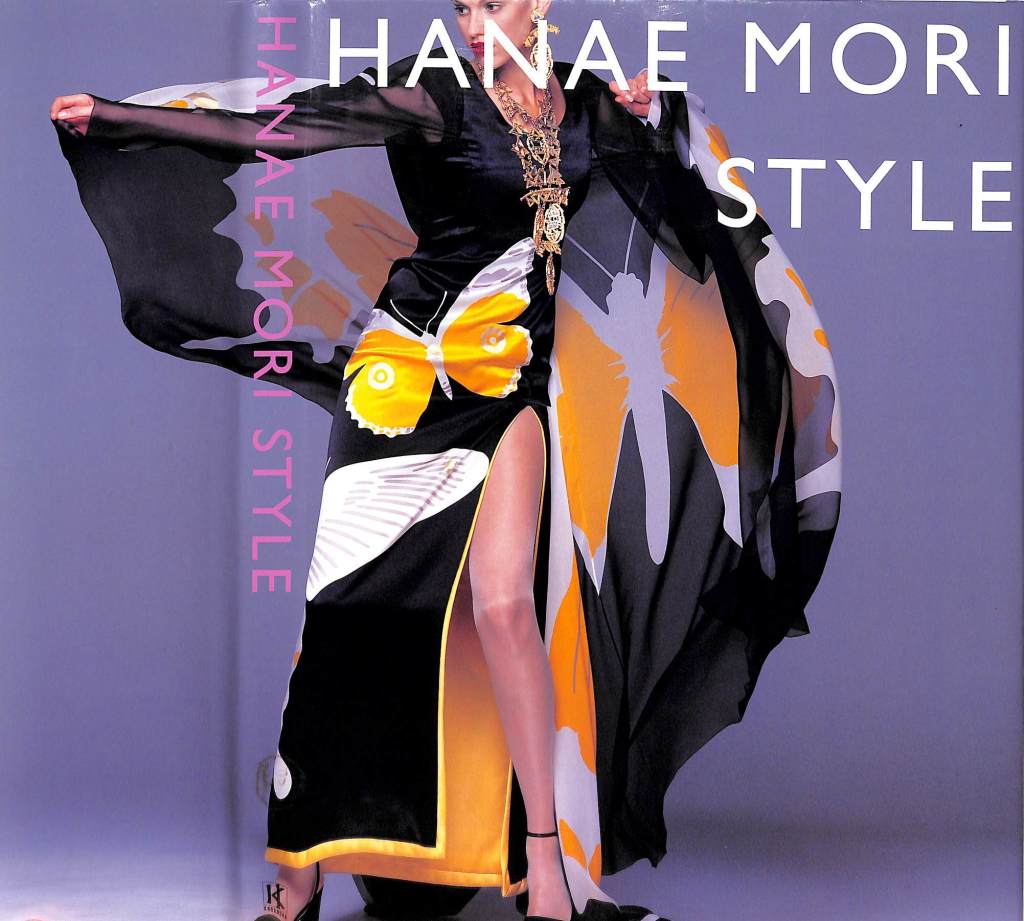

Butterfly flutter by…

We made mistakes in the 20th century. Who wouldn’t, with technology speeding everything up?

The 21st is even more dynamic and exciting but we can learn by thinking globally. Two great globalists, Issy Miyake and Hanae Mori have died this month, leaving legacies enriching lives across the planet, from East to West, probably, from North to South, too.

Making connections between the successful Japanese car market and Fashion in 2006, Akira Miura editor-at-large, Japan edition Women’s Wear Daily, expressed the idea that Hanae Mori, Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake & Rei Kawakubo were the ‘dazzling’ designers who had encouraged ‘the cloistered world of high fashion to look East’.

A subtle Fashion invasion was taking off. Toyota introduced the Corona sedan to the US in 1965, just as Hanae Mori presented her first collection in New York. It was a critical and commercial success as her ‘Japanese aesthetics,’ blended with Western forms and went on sale at important department stores.

Akira Miura, ‘Four dazzling Japanese designers inspired the cloistered world of high fashion to look East’

Hanae Mori opened boutiques in New York and Paris and became the first Asian to join the exclusive Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. Her reputation opened minds to the groundbreaking work and international style of later Japanese designers Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, whose creativity left ‘indelible impressions’ and indicated that, Asia could be a wellspring of inspiration, not just a base for textile mills and clothing factories.

Miyake’s stunning creations, ‘functional yet futuristic’ were frequently sculpted from a single piece of cloth. His influence spread to become a brand stamped on ‘luggage, home furnishings, even bicycles’.

Writing of how Comme des Garçons became a global phenomenon, in the 1980s, Akira Miura tells of how Rei Kawakubo brought her austere garments to the Paris catwalks in 1981 where they were seen as ‘almost anti-fashion’. Together with Yamamoto, their influence was so far-reaching that since then Fashion is identified as either ‘before’ or ‘after’ Comme des Garçons. Kawakubo told Miura, in 2006, that after reviewing a substantial number of her earlier pieces there was much she would ‘happily discard’, which prompted the WWD journalist to conclude:

“In an industry where reinvention and change is the only constant, that very un-Japanese dissatisfaction with the status quo has been an indispensable trait for all four of Japan’s great fashion iconoclasts.”

Modernise or What?

At the beginning of the 21st century our relationship with Modernism is complex.

The built environment we live in today was largely shaped by Modernism. The buildings we inhabit, the chairs we sit on, the graphic design that surrounds us have all been created by the aesthetics and the ideology of Modernist design.

We live in an era that still identifies itself in terms of `Modernism’ as post-Modernist or even post–post-Modernist.

Modernism was not conceived as a style but a loose collection of ideas. It was a term which covered a range of movements and styles that largely rejected history, and applied ornament, and which embraced abstraction. Born of great cosmopolitan centres, it flourished in Germany and Holland, as well as in Moscow, Paris, Prague and New York.

It was the British Post Office, which signalled Mary Quant’s greatness; putting a little black dress on one of a series of stamps, celebrating 50 years of Modern design in 2009. No one was more surprised than Mary Quant when she found herself in the company of celebrated 20th century Modernists.

Modernists had a utopian desire to create a better world. They believed in technology as the key means to achieve social improvement, and in the machine as a symbol of that aspiration. All of these principles were frequently combined with social and political beliefs (largely left-leaning), which held that design and art could, and should, transform society.

Let’s carry on leaning to the Left …………

8. Notorious Bricolage! (1940)

IN the movie, ‘Gone with the Wind,’ (1939) Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh) insists that her Mammy should turn her dead mother’s green velvet curtains into a fashionable dress to visit Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) in jail.

20th century cinema audiences gasped in horror as Scarlett rips the drapes from the elegant windows at Tara. The action became the most celebrated moment of invention, of make-do and mend, in the 1940s, chiming as it did, with women who knew how to make knickers, out of parachute silk!

“I’ll never recover from that first look,” David Selznick told his friends after he saw Leigh emerge from the embers of the ‘Burning of Atlanta’ set, costumed and made up to land the part of Scarlett O’Hara. As a snob and producer of the century’s most successful movie, he recognised that this instant would be life changing in his bid for Oscar winning glory.

Moments like this are at the heart of spectacular revolutions in the worlds of Art and Design, when lightening flashes of inspiration stir imaginations to begin spellbinding journeys to fame and fortune.

Women watching the movie say of Scarlett O’Hara, she is ‘powerful’ first and ‘beautiful’ second. She is determined to save Tara, her family’s cotton-growing estate in Georgia and like American pioneers was prepared to kill to defend her property.

To succeed, she has to take on male values and use her femininity to negotiate a power base while ceaselessly seeking the sexual fulfillment at the heart of the film’s romance.

She rips down her mother’s curtains to have them modeled as impressive, luxurious clothes to visit prison-bound Rhett Butler. She needs to borrow money to pay the taxes on Tara. It is not just an interesting piece of bricolage, Katie Scarlett O’Hara Hamilton is making ready to attack male bastions of barter and commerce with trappings of fetish and desire.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Camille Paglia leads a new generation of ‘Equity Feminists’ who are keen to throw off the acrimony between the sexes which began in the 1950s. While supporting equality before the law and the removal of obstacles to women’s advancement she also opposes special protections for women.

Paglia maintains that her reforming wing of Feminism is growing and gathering momentum from younger generations who are not in sympathy with judgemental, anti-pleasure, 20th century Feminism. It is my belief that the character of Scarlett O’Hara, supported by Rhett Butler in the film Gone With the Wind, is the prototype for our post-Feminist woman and that the film set the scene for romantic, feminine, provocative dress, emphasising the differences between men and women’s body shapes.

The clue’s in the blog not the look!

FRIENDS Anita, Fran and Lynne have Fashion coursing through their veins. They may spot Dior DNA, in abundance, in Maria Chiuri’s Ready to Wear collection, shown in Rodin’s Paris museum, this week.

Time is playing more tricks than usual during this pandemic. It seems such a short time ago that Maria Chiuri was the new girl at Dior. Yet since then my lovely sister, Ann, and my charming friend Fran have sadly died and are missed every day.

It wasn’t easy for me to find many clues in Chiuri’s Ready to Wear in the way my three friends were able to, but I thought maybe this black and white ensemble has a suggestion of Dior’s legacy in the darted waist, floaty skirt, peplum and tailored cuffs.

But here’s the rub: regardless of whether the critics like the clothes or see work as credibly linked to Dior’s back catalogue, sales are…

View original post 173 more words

Punk pranks, wild dreams, and Anglomania at the Met

Shown at Olympia in Spring 1987 Harris Tweed was Westwood’s first show for two-and-a-half years. The move towards a more traditional, fitted look had started in the summer, and in the Mini-Crini, collection she could explore the potential of British fabrics and styles in Harris Tweed…. She paid homage to the tailoring traditions of Savile Row and the jacket she designed then, named the Savile jacket, still features in her collections today.

VIVIENNE WESTWOOD told listening admirers at the opening of her retrospective in Sheffield in May, 2008, that the underwear as outerwear was Malcolm McLaren https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malcolm_McLaren ‘s idea. She was reflecting on British Fashion influence over the rest of the world. Anthropologist Ted Polhemus, said the British were renowned for ‘wild Fashion.’ Hat designer, Stephen Jones, thought that Fashion would not be the way it was unless Vivienne Westwood ‘had been around,’ and Anna Wintour, US Vogue, clinched the concept with, ‘I think the English designer is afraid of nothing.’

Later that year the V&A Vivienne Westwood retrospective set off from the Pennine hills, once again on its overseas journeys to set bells ringing on cash tills around the Pacific Rim. Whatever Westwood and McLaren set out to do, politically, in the 1970s they could not have realised how their project would grow to become a dynamic 21st century commercial success; and that an academically inspired exhibition, celebrating their vision, would travel round the world continually on view for more than five years.

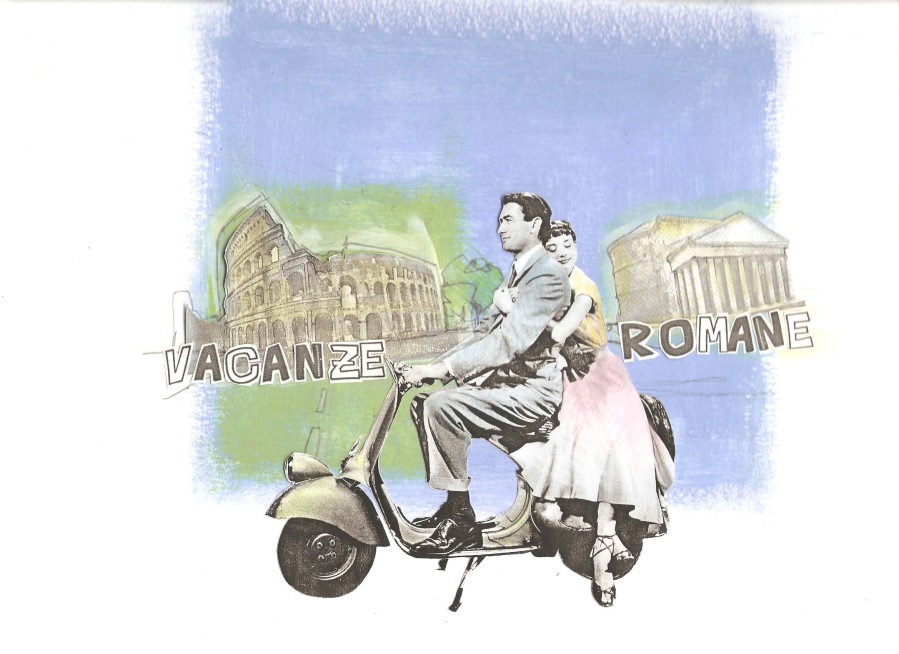

Favourite things….Audrey Hepburn and Breakfast at Givenchy’s

ONE magical turning point in Fashion’s fortunes was the release of Audrey Hepburn’s first significant Hollywood hit, ‘Roman Holiday,’ 1953. In Roland Barthes, Mythologies, his devastating take on consumerism and audiences, he describes Audrey Hepburn’s face as an ‘event.’ She had starred in only four major Hollywood films when she caused the French maestro and dilettante such sensation.

Barthes was proposing AH could represent meaning to audiences beyond those who watched her movies. After her most significant films were released, in the 1950s and 1960s, she became an influence on Fashion followers in Britain and America, encouraging women to use home dressmaking in the class struggle. As 21st century fans view Roman Holiday, Sabrina, Funny Face and Breakfast at Tiffany’s they witness the face that launched a thousand web sites and her popularity persists through digital media.

Audrey Hepburn stars in the second chapter of ‘FASHION MEDIA PROMOTION’ the collaboration between me and wonderful, Fashion illustrator and teacher, Anton Storey. ‘Vacanze Romane’ is based on a postcard, I had lying around. It was absolute genius for Anton to put the words from the back of it, which happened to be in Italian, across the main image. Super commissioning editor, Madeleine Metcalfe, who put her faith in me, also adored this pic. It was pinned above her desk when I visited her at Blackwell’s in Oxford.

At the political heart of ‘Roman Holiday’ is the script by Dalton Trumbo, part of the Hollywood Ten, the 10 motion-picture producers, directors, and screenwriters who appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee in October 1947, who refused to answer questions regarding their possible communist affiliations, and, after spending time in prison for contempt of Congress, were mostly blacklisted by the Hollywood studios.

‘I’ve never been alone with a man before’ the fictional Princess Ann (Audrey Hepburn) tells the newsman Joe Bradley, (Gregory Peck). For the audience, there is dramatic irony, realising that an heir to a throne is wearing borrowed pyjamas. He only realises who she is when he hears the news about her disappearance, next day. In a scene between Joe Bradley and his editor they discuss angles and trends. ‘Youth must lead the way,’ he is told. In 1953, this was a topical theme in the context of access to a young princess. Her observations, on world conditions, would be worth a fee to the journalist, of $250, but her ‘views on clothes worth a lot more, perhaps a thousand’. From that cinematic moment on, Audrey Hepburn would represent the dynamic interaction between Fashion and class structures. It was to be both her on and off-screen character; a role in which she would demonstrate how position in society dictates how Fashion is consumed.

Shopping with the Shocking Schiap

ELSA SCHIAPARELLI went from riches to rags and back again. Her signature Pink colour and perfume, ‘Shocking,’ were inspired by begonias, viewed from a pram in the grounds of her parents stunning Italian pallazzi. She spent a substantial living allowance; socialising in Europe and New York, so had to find ways to support herself and her daughter. And it just couldn’t be by designing a jumper and becoming a Surrealist.

Again and again Schiaparelli blazed new trails: she was the first conceptual designer, the first to do thematic collections, the first to produce fashion shows as spectacle and entertainment rather than glamorous business appointments. She was the first couturier to use man-made fabrics and to replace buttons with zippers, and the first designer of any kind to issue press releases. But more than anything else, she was the first to understand the power of marketing.

In 1933 Schiaparelli opened her own London salon and began featuring British woollen fabrics in her collections; tweeds and hand-knits, loving Scotland with its tartans, bonnets and tams. This sourcing of British textiles was a practice taken up by clever creative descendants Jean Muir and Vivienne Westwood. Her career prospered through her alliance with the British film and theatre industry and between 1933 and 1939 she designed costumes for 30 films and plays.

By 1935 the business woman in Schiaparelli was flourishing. She and her talented, American, public relations supremo, Hortense Macdonald, took a stand at the first French trade fair in Moscow. As sole representatives of French couture, they lined their booth with press-clippings printed on silk, with the floor covered in exclusive, Colcombet’s black ‘tree-bark,’ crepe with a fan-shaped display of international Fashion magazines. Writing for a student pack, which accompanied the 2003/4 Philadelphia exhibition, curator Dilys Blum captures the excitement of the Art Deco era:

“Since 1935, Schiaparelli had been presenting thematic collections at her salon, theatrically staged with dramatic lighting, backdrops and music. A fashion editor who regularly attended these events recalls that the front rows were filled with royalty, politicians, artists, film stars who pushed towards the models ‘as if it were rush hour’